Levesque spent the last three years of the war as a POW at Stalag Luft III along with more famous pilots such as W/C Bob Stanford Tuck. He never spoke much of his experiences as a POW. It was from this camp in March, 1944 that the "Great Escape" was made by 76 men. Most were caught and 53 were executed by the Gestapo. Levesque participated in the tunnelling but was not chosen for the escape.

Omer was back in the UK by June, 1945 and quickly took a refresher flying course. By July he was back in Canada for a well deserved rest and reunion with his family. He decided to attend McGill University in Montreal in the fall of 1945. He re-enlisted with the RCAF in 1946 and was posted to Rockcliffe in Ottawa, but was granted leave to finish his degree in political science and economics at McGill University.

He spent 1948 flying a C-47 Dakota with 414 Squadron in the north before he was posted to 410 "Cougar" Squadron in St. Hubert, Quebec. They had survived the post war cuts and had been changed from a night fighter squadron to a day fighter squadron flying newly acquired DeHavilland Vampires.

He quickly adapted to the nimble Vampire becoming one of the 410 Squadron's aerobatic team. They called themselves the Blue Devils. F/L R Schultz, F/L Don Laubman, F/O Mike Doyle, F/O Omer Levesque, F/L W Tew and S/L R Kipp OC were the members.

In his continuing series of "firsts" he made the fastest trip between Montreal and Ottawa in 8.5 minutes on May 9, 1949 in a test to see how fast and how far the Vampire could fly.

June 1949 was their first airshow appearance at Rockcliffe, with a second show at St. Hubert the same day. They were still practicing rolls and formation flying while travelling back to St. Hubert for the second show. They flew at many shows around Ontario, Quebec and the NE USA. On July 22 S/L R Kipp and Joe Schultz were practicing low-level aerobatics at St. Hubert when Kipp crashed and was killed. On August 28 at Brantford, Ontario Omer lost a wheel on takeoff. In spite of it, he flew the show and then carried on to Downsview just north of Toronto, where he made a successful belly landing. The team was disbanded at the end of the 1950 season, only to be brought back together in 1951. They were finally disbanded in August, 1951.

Life in the post-war RCAF wasn't all joy riding at air shows. The cold war was getting frigid and North American air units cooperated in joint exercises in the Yukon and Alaska preparing for the anticipated Russian invasion. Omer participated in Operation Sweet Briar in Feb. 1950 flying Vampire jet fighters. This was an Air Defence Group exercise designed to be a real test of the squadron's tactical mobility. It involved moving supplies, ground crew, bombers, reconnaissance aircraft, logistical aircraft and fighters from Ontario to the Yukon where they were to engage "the enemy" American fighters posted at Ladd Field, Alaska. They were flight planned from North Bay, Ontario, Fort William, Ontario, Rivers, Manitoba, Edmonton, Alberta, Fort St. John, Alberta, Fort Nelson, BC, Watson Lake, BC and finally Whitehorse, Yukon Territory. North Stars preceded the Vampires with supplies and ground crews. Some of the other pilots in the exercise he knew from training or the war, including Don Morrison and Don Laubman. The war games over the Yukon and Alaska included raiding the opposition ground installations and intercepting each other's aircraft. F-82's, F-80 Shooting Stars and Vampires were the primary fighters, although P-51s also took part. A-26s, C-54s, C-47 Dakotas and C-82s provided logistical support. Mitchells, Lancasters, and RF-80s may up the "bomber and recon force". During Sweet Briar he learned that he had been accepted for an exchange posting with the USAF. "They wanted to send me to England to fly Meteors with the RAF, but I didn't want to fly that bloody old plane. I wanted to go to the United States where they had the new planes."

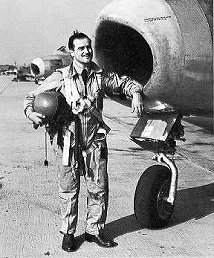

By May he was at Langely AFB, Virginia on an RCAF/USAF exchange program getting his check-out on the new F-86A Sabre with the 4th Fighter Wing. The Sabre was a revelation of how good and fast jet fighters could be. The Vampire in comparison with the Sabre was a weekend toy. He said of the Sabre, "It was like being on a bucking bronco - I didn't ride it, I just hung on! It had lots of power and could turn around on a dime. When you pull back you get a whole lot of air - the stabilizer doesn't fight the elevator. This made the aircraft tremendous."

On June 25, 1950 North Korea invaded South Korea with 90,000 troops. On June 27, the United Nations Security Council approved a resolution which recommended that UN member nations provide assistance to the Republic of Korea in repelling the armed attack against its territory. Three days later, President Truman authorized US aerial forces to attack military targets inside North Korea. American troops were committed to protect the south. China pledged to aid their fledgling communist neighbours and the Russians threw in with them as well. A superpower confrontation was under way with the United Nations supporting the American action, dubbing it the Korean Police Action.

The North Korean troops pushed south quickly, occupying Seoul in short order and pushed the Americans back to Pusan on the south coast. The Americans held out in Pusan and retaliated by wiping out the North Korean Air Force with WWII vintage fighters and a few obsolescent jet fighters. They bombed bridges, and troop concentrations so as to isolate the troops around Pusan. The North Koreans lost many of their invading troops. B-29 Superfortress bombers destroyed most of the North Korean industrial capacity. General Douglas MacArthur and his American troops landed at Inchon and completely isolated the North Koreans. Then American and other UN troops advanced steadily into North Korea until in November, 1950 the Chinese entered the war with masses of troops and Russian-built MiG-15 fighter-interceptors. This new fighter was fast, agile and powerfully armed.

In days five bombers fell to their guns and others were badly damaged. It quickly became apparent that the F-80 Shooting Stars could not protect the B-29s as they were badly outclassed by the MiGs. President Truman was forced to commit a front-line fighter unit with F-86 Sabres, the 334th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, to the war zone. By December, 1950 Omer was in Korea with another full-blown war raging around him. Eventually 21 other Canadians would follow him into the air war over Korea flying with American units.

With the Chinese involvement in the war the UN land forces withdrew successfully to a defensive line across Korea south of the 38th Parallel. A new military strategy was then adopted--maintain superiority in the air while inflicting maximum damage to the enemy on the ground, thereby making war so costly that they would request an armistice.

Much of the success of this new strategy depended upon close air support to UN troops. Daily, USAF F-84 Thunderjet fighter-bombers attacked every conceivable type of target on the front lines and in rear areas with machine guns, rockets, high explosive bombs, and fire bombs. At the same time, B-29 Superfortresses pounded the North Korean rail and road networks to isolate Communist troops from their supply sources, attacks so devastating that traffic in North Korea could move only at night. All of this bombing required air support from F-86 Sabres to keep the MiGs at bay.

| In December 1950, as a Flight Lieutenant, he became the first Canadian to fly operations in Korea. The 334th Fighter Interceptor Squadron was based at Kimpo about 200 miles from the Yalu River separating Korea and China. He earned the US Air Medal by flying 20 missions from the 17th to the 21st of December, roughly four a day.

LEVESQUE, Squadron Leader Joseph Auguste Omer (17794) - Air Medal (United States) - awarded as per AFRO 490/51 dated 10 August 1951, "in recognition of meritorious achievement while participating in aerial flight from 17 December to 21 December 1951." |

A peculiar situation existed during the Korean Conflict with respect to the air war. Not only were UN aircraft prohibited from attacking MiG bases across the Yalu in Manchuria, but MiG-15 pilots were prohibited from attacking UN positions from their Manchurian bases. These restrictions were developed to avoid a direct confrontation between American and Chinese forces that could escalate the Korean War into WWIII. However, there was no such restriction on MiG pilots if they took off from airfields in North Korea. Consequently, the Communists decided to repair damaged airstrips in North Korea in addition to building new ones in order to take advantage of this situation.

As the MiG airfields neared completion in April and May 1951, B-29s carried out an intensive bombing campaign and destroyed them. During the same period, USAF B-29s cut most of the bridges across the Yalu. However, these WWII propeller-driven bombers became so vulnerable to the modern MiG-15 jet fighters during daylight missions, even with area cover provided by USAF jet fighters, that by late 1951, they began operating only at night.

|

On March 31, 1951 Omer Levesque was the first Commonwealth pilot to shoot down an enemy MiG 15 jet in Korea. The following, rather dramatic, account is by Mike Minnich published in Air Classics: The bright winter sun dazzled against the cobalt blue sky. Outside the cockpit of Levesque's Sabre, the temperature was - 60 F. At the patrol altitude of 40,000 feet, an oxygen system failure could mean unconsciousness in 30 seconds and death within minutes. Omer Levesque was getting used to the strange world of high-altitude, high-speed jet combat. Since arriving in Korea in December, he had flown more than 50 combat missions. This day's task was typical. A large formation of American B-29 Superfortress propeller-driven bombers was attacking bridges spanning the infamous Yalu River, the bounday between North Korea and its ally Red China. Two squadrons of Sabres were assigned as escorts, to protect the bombers from any MiGs that might attempt interceptions from their bases in nearby "neutral" Manchuria. The Sabre formations were weaving, attempting not to outpace the much slower B-29s. Levesque's gaze travelled past the bulge of his tightly fitting oxygen mask to scan the 24 instruments and dozen indicators that revealed the vital signs of his F-86s operation. "I was flying as wingman for Maj Ed Fletcher, leader of Red flight, " Levesque remembers. "Suddenly the squdron commander called out bandits coming in from the right. We all dropped our auxiliary fuel tanks and Fletcher spotted two more MiGs at nine o'clock - off our left wings and above us a bit." The two pilots turned sharply towards the pair of enemy fighters, who quickly split up and turned away to evade the pursuing Sabres. "My MiG pulled up into the sun, probably trying to lose me in the glare," Levesque tells. "That was an old trick the Germans used to like to do - but this day I had dark sunglasses on, and I kept the MiG in sight." The enemy pilot - many of whom were Russians, although none were ever captured for absolute proof - levelled off, not knowing Levesque had stuck on his tail. The tenacious Canadian quickly adjusted his illuminated gunsight for a deflection shot and banked more steeply to turn inside the MiG. The corkscrewing dogfight had by then carried them down to 17,000 feet. Levesque's right index finger tightened on the control-stick trigger and sent six streams of .50 calibre bullets streaking home. "I guess I was about 1500 feet away from him," he says. "I hit him with a good long burst, and he snapped over in a violent roll to the right. I must have hit his hydraulic system, because I saw the flap on his left wing drop down alone." |

The MiG 15 kept rolling straight into the ground. A flash of red flame and white smoke marked the funeral pyre of plane and pilot.

"I started to pull up, and saw another MiG diving from above me," Levesque says. "I climbed into the sun at full throttle and started doing barrel rolls . The MiG dissappeared".

The constricted bands of Levesque's G-suit relaxed their hold around his legs and waist as the G-forces of his sharp pull-up diminished. Without the device, blood rushing from the head in such manoeuvers would cause the pilot to black out.

Soaked with sweat, he noticed that his fuel was approaching "bingo," the point where 1000 pounds remained - just enough to get him safely back to base at Suwon, South Korea. Turning his F-86 southwards at the fuel-efficient height of 40,000 feet, he could relax a bit. It had taken 10 years and two wars, but Omer Levesque was an ace at last.

In Omer's words the fight was somewhat different. "I got in a really nice deflection shot but with those six guns firing you lost 30 to 40 knots of speed, which was a hell of a lot! I aimed again and fired another burst and, all of a sudden, the flaps came down on the MiG. He kept on turning and I followed him down." He was nearly blacking out, even with his compression suit helping out. Firing again, he raked the MiG from nose to tail and watched as it rolled end over end into the hills below.

Even after losing the second MiG he wasn't safe. "I went right through the B-29 formation and they all shot at me! Thank God they missed. I waggled my wings and they stopped firing, but lots of shells had just missed me."

He received the United States Distinguished Flying Cross for his combat. The following is an excerpt from DFC (US) citation, quoted in an RCAF Press Release of May, 1951.

Flight Lieutenant JAO Levesque, RCAF, performed an act of heroic and extraordinary achievement as a member of a flight of four F-86 type aircraft on a combat air patrol south of the Sinuiju-Yalu River area, North Korea. Flight Lieutenant Levesque's flight engaged enemy high performance jet aircraft in a battle which varied in altitude from 30,000 feet to 3,000 feet. Through aggressive and skilful maneouvering, he made repeated daring attacks upon the enemy which resulted in his personal destruction of one enemy aircraft. His brilliant evasion of other enemy aircraft added immeasurably to the success of his mission. Flight Lieutenant Levesque's heroic and extraordinary achievement and meritorious devotion to duty has brought great credit upon himself, his comrades in arms of the United Nations, the Royal Canadian Air Force and the United States Air Force.

His American awards were presented at Johnston AFB, Japan, January 1951. With 71 operational sorties under his belt with the 334th he was rotated home in June 1951. He was proud of the Canadian contingent in the US Air Force and of the entire UN air force efforts in general. "We achieved absolute air superiority in Korea. It was just classic. The Chinese said afterwards that they would have gone over us like a steamroller if it hadn't been for the Allied air force."

In July, he took up duties at CFB Chatham as the CFI (Commander Fighter Instructors) with No. 1 (F) OTU. He was awarded the Queen's Coronation Medal in 1953. Later he flew Canadair Sabres with 4 Wing in Europe and worked at Air Division HQ in Metz. While there he was instrumental in securing the French base at Rabat for the RCAF as a gunnery base. The deal was cooked up over a bottle of beer. The French officer promised that if Levesque got him a check-out on the Canadair Sabre, he would see that a deal for Rabat was taken care of.

He later returned to Canada flying Vampires with 438 Squadron, worked at Air Defence Command in St. Hubert, did a tour with the International Control Commission in Vietnam, meeting both Ho Chi Minh and General Vo Nguyen Giap during a visit to Hanoi. He then worked in the NORAD system. Following his Air Force retirement in 1965 he worked on the Air Transport committee in Ottawa until 1987. He still lives in Quebec.

While not being a high scoring ace, Omer Levesque demonstrated an overwhelming ability to be first in military aviation of his times, and a decided mental toughness that kept him going even after he had been shocked by the bloody and sudden nature of aerial warfare. Few would have returned to flying after three years in a POW camp. Fewer still would have worked their way into the ranks of the best pilots in their airforce and back into a major international war. Omer Levesque did. He just couldn't quit.

This page is located at

http://www.grostenquin.org/other/gtother-246.html

Updated: January 16, 2002